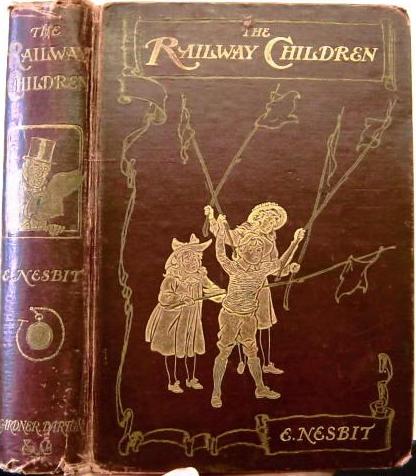

In listening to E. Nesbit’s The Railway Children published in 1905 (audio available for free on Librivox), I noticed something very interesting. British children at the turn of the century, at least according to Nesbit, were not supposed to show emotions, and these emotions were on the whole very embarrassing. In modern American literature for children, emotions are big and important and very much worthy of thought and expression. This contrast is fairly stark. To illustrate, here are some dueling quotes. The first set is from The Railway Children. The second set is from Completely Clementine by Sara Pennypacker, published 110 years later in 2015, which I chose as representative of current mid-grade fiction.

Oh—” and then she went on and said all sorts of things that I won't write down, because I am sure that Peter and Bobbie and Phyllis would not like me to. Their ears got hotter and hotter, and their faces redder and redder, at the kind things Mrs. Perks said. They felt they had done nothing to deserve all this praise.

“It’ll hurt rather, won’t it?” he said. “I don’t mean to be a coward. You won’t think I’m a coward if I faint again, will you? I really and truly don’t do it on purpose. And I do hate to give you all this trouble.”

“Come in, Daddy; come in!” He goes in and the door is shut. I think we will not open the door or follow him. I think that just now we are not wanted there. I think it will be best for us to go quickly and quietly away. At the end of the field, among the thin gold spikes of grass and the harebells and Gipsy roses and St. John’s Wort, we may just take one last look, over our shoulders, at the white house where neither we nor anyone else is wanted now.

As you can see in the above quotes, even pleasurable feelings such as pride in a job well done or loving reunion of a family is portrayed as something shameful to be hidden away, and experienced only in private.

By contrast, here are some passages from Completely Clementine:

Then I crossed out “Crying” and changed it to “weeping.” This is because weeping is a lot sadder than crying; it’s tragical really. I like to use the right word for things.

“You need to start talking to your dad.” My clay suddenly looked like a teardrop. I squished it into a ball. “I want to. I miss him so much. But I don’t think I can anymore.

He hugged me, then he hugged Maria and Rasheed. Then he apologized for hugging us. Then he took of running around the playground high-fiving everybody else. When he ran out of kids to high-five he leaped up and punched the air. “Yes!” he shouted.

In Completely Clementine, emotions are important things to be communicated about as clearly as possible, and felt deeply and openly. What a difference a century makes!